The 6th European Healthcare Design Congress continued on day two with another plenary of keynote talks, exploring wider issues around health, wellness, life expectancy, health inequalities, and how technology may be deployed to address these problems.

Lord Nigel Crisp, co-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health and a former NHS chief executive, explained how there is a tendency in the UK and elsewhere to think that the NHS equals health, or health equals the NHS, or health equals the health system.

“It’s often about ill health and the causes of disease, and countering them,” he said. “I want to talk about the other side of that: health creation and the causes of health.”

Health is made at home, hospitals are for repairs

Indeed, these dynamics are the focus of Lord Crisp’s latest book, Health is made at home, hospitals are for repairs, published earlier this year by SALUS.

“The reason I wrote it,” he explained, “was to celebrate the thousands of people, such as teachers, employers, community leaders, and indeed architects, developers and entrepreneurs – all the people who are not health professionals but who are actively improving health and wellbeing. And I wanted to understand what they were doing and what it meant for the future.

“The pandemic has reinforced this and shown the different roles that everyone plays in health – in the health system, government, and by each of us as citizens. There will continue to be a role for us all in health once the pandemic is over or contained because the NHS and health system can’t do everything by itself. It can’t deal with many of today’s problems, such as loneliness, stress, obesity, poverty and addictions. It can only react, doing the repairs but not addressing the underlying causes.”

The people who are addressing these underlying causes are the health creators – people in business, education, in communities and the voluntary or charity sector, who are opening up new ideas of health creation and quality of life. Lord Crisp stressed that these people “aren’t waiting for professionals or government to tell them what to do but they’re breaking new ground, taking the initiative and leading”.

He went on to distinguish health creation from health prevention, describing that latter as about the causes of ill health and dealing with problems, while the former is positive, much more holistic, and about dealing with the causes of health and broader human flourishing.

COVID-19, said Lord Crisp, has accelerated several trends in healthcare design that were already in play prior to the pandemic. These include more care in the community and at home, delivered in part through the use of technology, and greater awareness of the importance of greenery, the environment, gardens and nature.

There is greater focus around issues such as patient power, too, and the health creation movement will accelerate that. Said Lord Crisp: “It’s great that around the country there are more health and care centres, which have community facilities, but actually I’d like to see that the other way around – community facilities that have health within them.”

And the use of technology in delivering health has also received a boost from COVID, with the implications that wearable devices in the future might be used to give constant feedback on health, impacting in various ways on patient empowerment.

But Lord Crisp believes there’s something deeper and more human going on, too – a real focus on communities spurred, in part, by increased solidarity around the common cause of fighting COVID. This community focus is well aligned with the work of the health creators, whose activities centre on relationships, meaning and purpose, learning by doing and experimentation, on people having control, and building on strengths.

The NHS and government need to understand how to work with these people and their organisations, added Lord Crisp. They should be listening, not just engaging; supporting, not just telling them how to do things.

And he had a message for architects, designers and planners as well – that they need to think about the infrastructure that supports health creation, as well as the infrastructure that supports healthcare and health prevention. “There is great transferrable knowledge and skills from the people who understand healthcare to the people who will be able to support health creation, as well as prevention in our society,” he said.

The stalling of life expectancy and the increasing health gap

Related to the issues raised by Lord Crisp, Jennifer Dixon, chief executive of the Health Foundation, then took up the mantle of describing to delegates why life expectancy in the UK and in other countries around the world is stalling, and what can be done to address widening health inequalities.

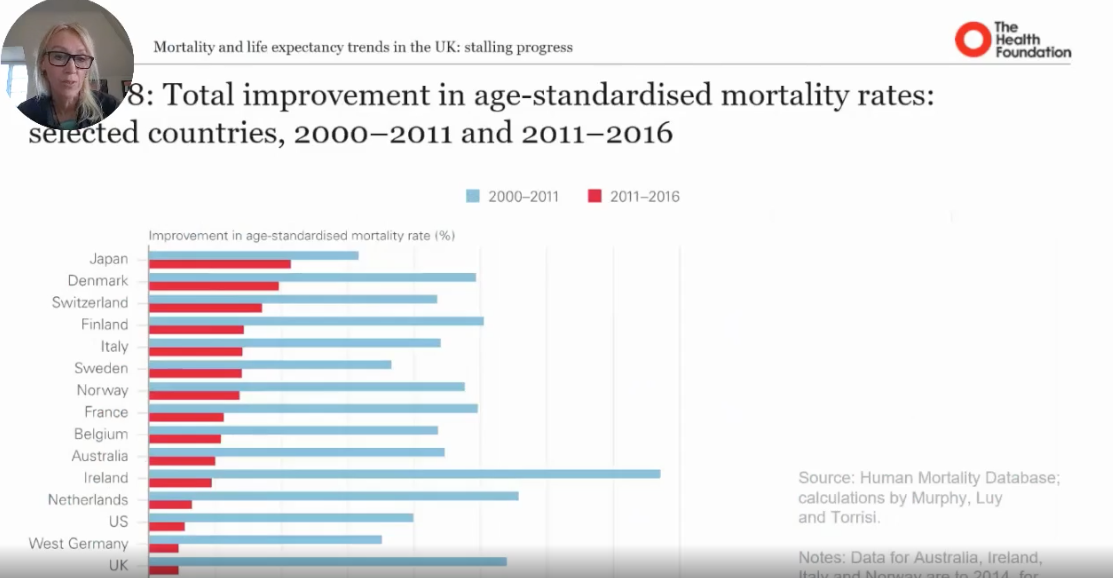

Showing charts on the total improvement in age-standardised mortality rates for a range of countries over two different periods, 2000-11 and 2011-16, she argued that something quite dramatic happened in the second period. There have still been improvements in life expectancy – a measure of the health of our population and the fabric of our health – but there has been a significant slowdown, and the UK has performed particularly badly in this respect. Indeed, some communities have even gone into reverse in regard to life expectancy.

Highlighting evidence contained in the report, ‘Health equity in England: The Marmot Review ten years on’, life expectancy for men in England during 2016-18 stands at 73.9 years for the poorest decile compared with 83.4 for the richest decile. But it’s not only that poorer people can expect to live shorter lives; men in the poorest decile also spend more years in ill health than men in the richest decile.

“Since 2011, whatever is happening and affecting the fabric of society in regard to health, it’s affecting poorer people the most,” said Dixon.

“Since 2011, whatever is happening and affecting the fabric of society in regard to health, it’s affecting poorer people the most,” said Dixon.

Part of the reason for the slowdown in mortality reductions can be put down to increased heart disease and stroke, while some bad winters have also impacted mortality in the last decade. But there are also other wider factors at play. One theory in the UK is that austerity is a primary cause of the life expectancy slowdown, but other commentators point to long-run structural changes to the economy, such as deindustrialisation, which have been hurting communities for many years.

Where government and other policy leaders focus attention is open to debate – do they focus on disease? Should they be looking at risk factors, such as targeting reductions in smoking or combatting obesity? Or should a wider approach be adopted, looking at pre-risk factors, such as the quality of housing, work, skills, education, etc. And within these areas, there are different agency levels, too – national, regional, local community, groups, and individuals.

The key thing, according to Dixon, is that action is needed across a variety of areas over a sustained period to bring about positive change.

Outlining the measures that could be implemented to narrow the health gap, Dixon argued for a big agenda approach involving:

- cross government national policy – the economy of wellbeing, accountability of population health;

- commitment devices – legislation, accountability, transparent comparative rounded measurement, investment in health;

- cross-sector action: central government, local government, healthcare systems, business and tech, investors, voluntary sector;

- focus on short- and long-term targets; and

- commitment and collaborative leadership.

In regard to healthcare providers, added Dixon, there is a lot of work going on in the UK and in the US about hospitals as anchor institutions. How can the NHS sweat its assets to help the community do more to improve people’s health? Measures here could include purchasing more locally for social benefit; using buildings and space to support communities; widening access to quality work; working more closely with local partners; and reducing hospitals’ environmental impact.

Health and wellbeing in socio-technological ecosystems

After two presentations providing a research and policy focus on creating health within communities and addressing health inequalities, the final keynote speaker, Alberto Sanna, from the San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Italy, offered some research and practical insights into how technology might be deployed to enhance health and wellbeing.

Sanna explained that the challenges of ageing societies and rapid urbanisation of populations have led increasingly to unhealthy and unsustainable lifestyles. These challenges, he argued, can be only addressed with a complete, progressive and coherent redesign of the entire social, technical, economic and environmental ecosystem.

With rapidly growing emerging and converging technologies, including the Internet of Things, robotics, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and 5G, there is a need to urgently shift our mindset and apply technology as an enabler, not only to promote and create health and wellbeing but also to prevent our healthcare systems becoming overburdened.

According to Sanna, the ecosystem that promotes us to be healthy in our everyday lives and the healthcare ecosystem that treats us when we’re sick are often out of tune with each other. Yet they’re the most critical ethical consideration because of the possible implications of such transformation. And there are human factors to consider, too. Technology, said Sanna, must be a means to better health, not an end in itself. It’s impossible, he added, to force through the transformation of a human-centred ecosystem without fully convincing and engaging the participation of doctors and caregivers, individuals and communities.

He went on to explain the work of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute’s Research Center on Advanced Technology for Health and Wellbeing, which runs European and industrial multidisciplinary research projects based on co-creation methodologies in the Open Service Innovation Living Lab of the San Raffaele Hospital and Smart City. Sanna provided several practical examples of projects and pilots from three research programmes: Smarter and Safer Hospital; Smarter and Healthier Life; and Smarter and Healthier City.

One project considered patient adherence in self-care by means of a Smart Care Cabinet. The idea behind this is to use a smart medicine cabinet to feed information to patients so they are in control of when they have to take medication, whether the medication has expired or not, and if the medication is compatible with some food they intend to eat. “This gives motivation to the patient to adhere to the prescription, as well as giving information to the doctor on adherence,” explained Sanna.

Another example is a project that sought to provide personalised information on food purchases at the supermarket on the hospital’s premises. Shoppers put the food into a smart trolley and in real time, a blue food label turns red (alert), green (ok) or yellow (warning) to indicate if the food is compatible with a healthy diet for that specific individual.

“This is a referral that the hospital is getting to you in real time, based on the scientific knowledge we have and about the food in respect of your own health,” said Sanna. “Comparing what you are buying with what you may need, like, and so on and so forth.”

A further project is focused on the issue of wellbeing in mobility by means of a personalised vehicle. Here, the interface between the human and the car is designed to limit the cognitive effort, so more time can be devoted to safety. Along with an innovative human-machine interface based on gesture recognition, the operation of the auxiliary systems has been simplified; the on-board display design is based on advanced cognitive science studies; and optimal posture, including lumbar and neck support, has been considered for comfortable and low-fatigue driving. In addition, a robotic chair has been designed to allow for easy egress and ingress through a 90-degree swivel capability. And an assisted rear e-lift function supports easy loading and unloading into or out of the vehicle.

Summing up, Sanna was quick to stress that privacy and civil rights must be put at the centre of technology. “If we leave data in the hands of big companies,” he warned, “we will have big problems, because data is the way you can manipulate behaviour.”